The simplistic beauty of a perfect round brilliant cut diamond sitting proudly, tightly held within the arms of the claws – or embraced by a collet setting.

But is it simple really?

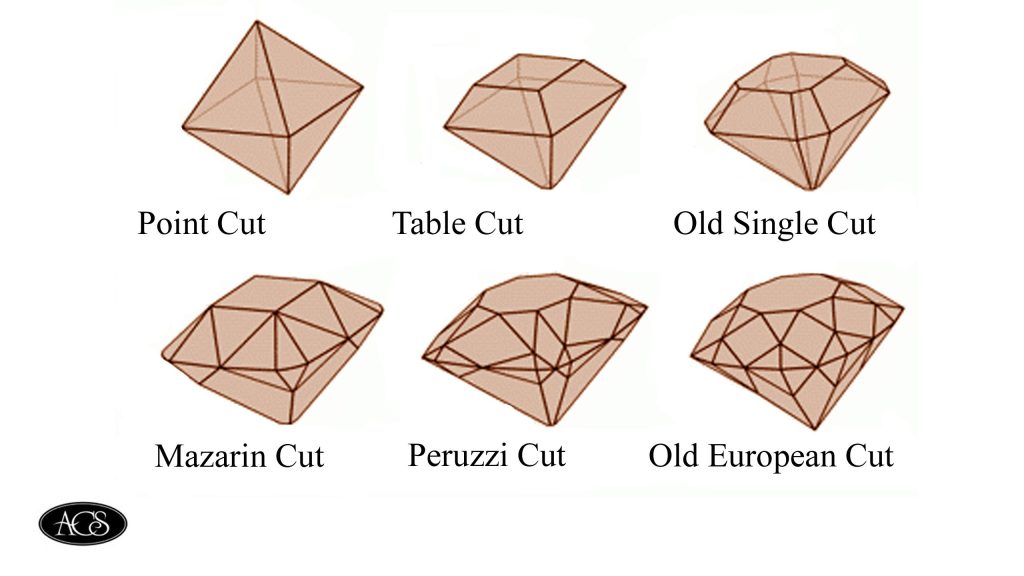

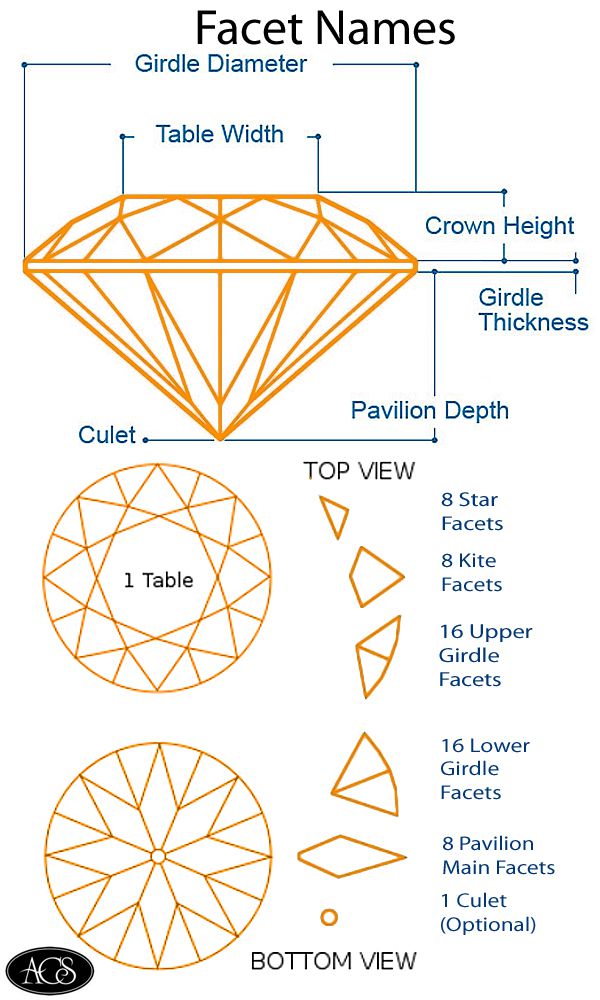

A modern brilliant round diamond is cut and assessed on specific dimensions in order to produce the best return of light/fire. Modern brilliant cut diamonds are given a “cut” grade, as well as the expected colour, clarity and carat, which is judged not only on the specific dimensions but also the optical performance of the diamond.

These include:

- Scintillation

- Fire

- Pattern

- Brightness

- Polish

- Symmetry

The Gemmological Institute of America (G.I.A) provides a grading on the above combinations in addition to a “cut” grade.

The grades are defined as:

- Excellent

- Very Good

- Good

- Fair

- Poor

A Good All-Rounder

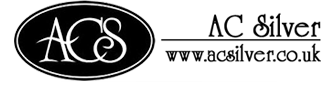

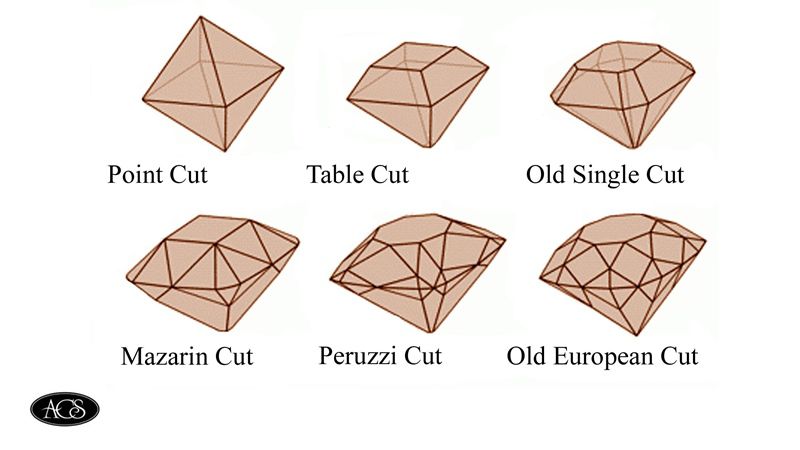

Over the centuries, we have seen the birth of many different types of diamond cuts, from the earliest, point cut, to the popular rose cut diamonds of the Victorian Era. These types of cut were used to enhance a diamond’s adamantine lustre rather than the return of light we know as ‘fire’ or ‘sparkle’. Through hard work, experience, and expertise, we have the modern brilliant cut diamonds produced today.

When we send a modern diamond to be graded, it is graded within specific dimensions. It is these properties that have been improved upon throughout the last 100 years.

When we come to grade older stones, it is unfair to assess the “cut” grading, as these stones were not cut to contemporary conventions. The grading system for diamonds was not introduced until the 1950s, and the cut grading system around fifteen years later.

At AC Silver, we are lucky enough to see the evolution of the round cut within our stock. We have a fantastic range of antique and vintage jewellery which incorporates not only Old European round cuts but also modern transitional round cuts (also referred to as circular brilliant cut by the GIA).

In order for the Old European cut and transitional cut to be excluded from a particular cut grade, they must come within their own dimensions.

For the Old European cut, the stone must meet 3 of the 4 shown below:

Table size:

Less than or equal to 53%

Crown angle:

Greater than or equal to 40 degrees

Lower half length:

Less than or equal to 60%

Culet size:

Slightly large or larger

For the modern transitional round cut, it must come within all three of the below parameters.

Lower half length:

Less than or equal to 60%

Star length:

Less than or equal to 50%

Culet size:

Medium or larger

Different Facets

The Old European round cut was a development on the more squared/cushion-shaped old mine cut, also known as the Peruzzi cut. The introduction of the steam driven Bruting machine by Henry D. Morse, which was patented 1874, facilitated the production of a more refined, circular shape. Morse also lowered the angles of the crown and pavilion in order to maximise a diamond’s brilliance.

In 1919, Marcel Tolkowsky – a gemmologist and mathematician – built on Morse’s’ findings. Tolkowsky studied and developed a mathematical formula as part of his doctoral thesis. The formula looked at the cutting and angling of the facets of the round diamond, again in order to maximise the brilliance/fire of the stone. Tolkowsky’s proportions have become the standard for cutting brilliant cut diamonds, as his dimensions allow for a more balanced dispersion-brilliance ratio.

Dating Jewellery by the Gemstone Cuts

The differences between particular cuts aid us when researching an item of jewellery. Basically, the steeper the pavilion angle, the older the stone, with newer stones having a larger table. For example, Victorian jewellery incorporates Old European cuts, whereas items created around the 1930s to the mid-1950s display transitional cut diamonds. As previously mentioned, the Old European cuts and transitional modern brilliants are not presently graded on their cut because they were created before this system was put in place.

There are many different people who have also contributed to the more contemporary “ideal” brilliant cut, so it is hard to identify an individual creator of today’s most common cut.

Opinions differ between gem grading laboratories and associations regarding the ideal brilliant cut, and this is demonstrated in the table below, which states the actual dimensions each company adheres to and the inherent differences this creates.

| Benchmark | Crown Height | Pavilion Depth | Table Diameter | Girdle Thickness | Crown Angle | Pavilion Angle | Brilliance Grade |

| American Standard | 16.20% | 43.10% | 53.00% | N/A | 34.5° | 40.75° | 99.50% |

| Practical Fine Cut | 14.40% | 43.20% | 56.00% | N/A | 33.5° | 40.8° | 99.95% |

| Scandinavian Standard | 14.60% | 43.10% | 57.50% | N/A | 34.5° | 40.75° | 99.50% |

| Eulitz Brilliant | 14.45% | 43.15% | 56.50% | 1.50% | 33.36° | 40.48° | 100% |

| Ideal Brilliant | 19.20% | 40.00% | 56.10% | N/A | 41.1° | 38.7° | 98.40% |

| Parker Brilliant | 10.50% | 43.10% | 55.90% | N/A | 25.5° | 40.9° | Low |

| AGA | 14.0 – 16.3% | 42.8 – 43.2% | 53 – 59% | N/A | 34.0 – 34.7° | N/A | 100% |