The influence of tobacco on popular culture and social norms has been substantial across various societies worldwide. While it may be less favoured today, its legacy is clearly reflected in the exquisite art and unique artifacts it has generated. Notably, the snuff box emerges as one of the most captivating examples.

While the contemporary consumption of tobacco is largely through cigarettes, cigars, or pipes, its initial 300 years of popularity in Europe saw it primarily used in powdered form for nasal inhalation. This addictive trend became a staple of social customs among the elite in the late 17th century, despite its tendency to provoke sneezing. Esteemed figures such as queens, nobility, and even popes were known to indulge in snuff, and, as with many elite practices, its widespread use called for elegant accessories that conveyed social standing.

16th-17th Century

The early adoption and widespread use of tobacco, especially in the form of snuff, originated primarily from medical intentions rather than for enjoyment.

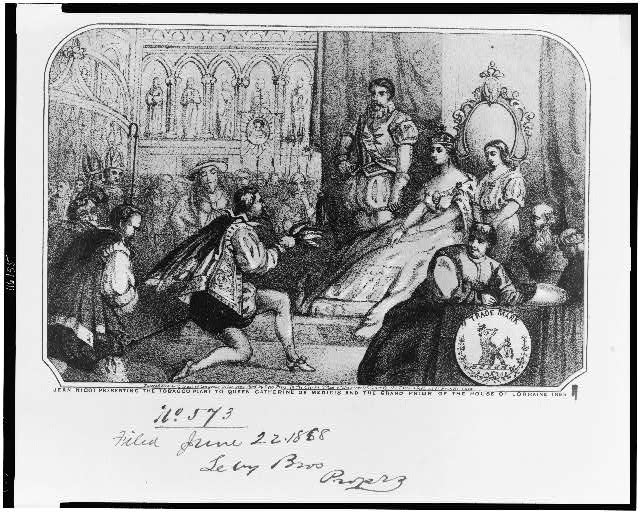

Jean Nicot, a French scholar and ambassador to Portugal, promoted tobacco as a cure-all for various ailments. Linnaeus later honoured him by naming the plant Nicotiana in recognition of his efforts. In 1561, Nicot presented tobacco to Catherine de Medici, recommending it as an errhine, or a nasal remedy, to address her chronic headaches. Impressed by its results, she named it Herba Regina, or queen herb, and continued to use it throughout her life. Her advocacy significantly boosted the popularity of snuff among the French elite.

During this period, the storage of snuff was quite simple, typically kept in small pouches and containers. As snuff gained popularity and became a fashionable pastime, the demand for specialised boxes for its storage began to rise.

17th – 18th Century

Recognising that prevention was more effective than treatment, snuff quickly evolved into a favoured recreational activity. By the year 1620, it had gained significant traction, particularly among the aristocracy. Its prevalence became so pronounced that in 1642, Pope Urban VII issued a papal bull, Cum Ecclesiae, warning of excommunication for snuff users. It was said that snuff consumption interfered with mass, as priests often kept their own snuff boxes conveniently on the altar.

Nevertheless, snuff maintained its appeal. Queen Anne of Great Britain (1702-1714) was known for her fondness for snuff, and it was customary for her court members to carry beautifully adorned snuff boxes crafted from porcelain, agate, ebony, and tortoiseshell. Some even kept snuff in the heads of their unique walking canes, which were vital accessories of the time. During Queen Charlotte’s reign, the act of taking snuff evolved into a collective pastime. People would gather to enjoy snuff together, sharing different blends of ground tobacco and displaying their ornate boxes. As the craftsmanship of snuff boxes became more intricate, they also became popular as gifts.

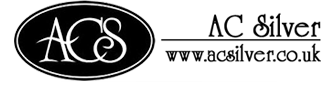

Early snuff boxes were crafted from precious materials like gold, silver, ivory, and mother-of-pearl, often encrusted with gems, adorned with intricate enamelwork, or featuring miniature paintings. Created by master artisans, these boxes became especially elaborate in France under Louis XIV and were highly favoured by English royalty like King Charles II and Queen Anne. Personalized designs reflected the owner’s tastes, with engravings of family crests, initials, or scenes depicting political allegiances and favourite pastimes. Our collection of gold boxes features a wide range of designs.

19th Century

In the 19th century, the use of snuff spread from the upper classes to the burgeoning middle class, prompting the creation of more budget-friendly snuff boxes made from wood, tin, and papier-mâché. However, the Napoleonic and Regency periods remained notable for the continued craftsmanship of exquisite snuff boxes, often given as diplomatic presents or tokens of love.

Late 19th-20th Century

By the end of the 19th century, the popularity of snuff started to wane as cigars and cigarettes became more fashionable. Consequently, the manufacturing of snuff boxes saw a decline.

The historical significance of tobacco, particularly in the form of snuff, has profoundly shaped social customs and cultural artifacts, exemplified by the intricate craftsmanship of snuff boxes that reflect the status and tastes of their owners. Although the use of snuff has diminished in contemporary society, the enduring appeal and collectability of snuff boxes as collectible items highlights their cultural legacy, certainly not an item to be ‘sniffed’ at.